TE ARAROA AND THE TIMBER TRAIL WITH BRIAN – OCTOBER 2022

It’s time to take Lalita on another adventure, because spring is here. The day of our departure is grey and damp. We’ve had lots of grey damp days here in Raglan, but the forecast predicts sun for tomorrow.

We drive out to Kaniwhaniwha which is only an hour away, for the night, a gentle introduction. I’ve stayed here many times with grandchildren but this will be Brian’s first visit. We are alone in the upgraded car park, right down the end, tail-gate into the trees, side door opening onto the roughly mown paddock. The familiar rawness of mud and gravel and broken bollards has been removed in an upgrade. I would like the roughness back, but never mind, I’m just happy to be away from my normal life. Stepping gingerly on the soggy pond lawn, surrounded by dark kahikateas under the moody, brooding sky is just what I need. Brian is doing his best. This is not so much fun for him.

I heat stew and rice and silverbeet for dinner, a normal dinner brought straight from home in plastic containers, but it tastes different, because we’re camping now, and all food tastes fantastic when eaten in the wild.

The night is fine, the morning okay although we get lost a couple of times on our way to Honikiwi Road, and this road, once we find it, is closed because of a slip, but we ignore the warning. We’re feeling a little desperate by now, and inch our way through.

Brian cooks up sausages and eggs under a blue sky at the road’s end, while I put chairs out on the gravel and make the coffee. I’m hoping all our trials are over. The bush I am so desirous of is all around.

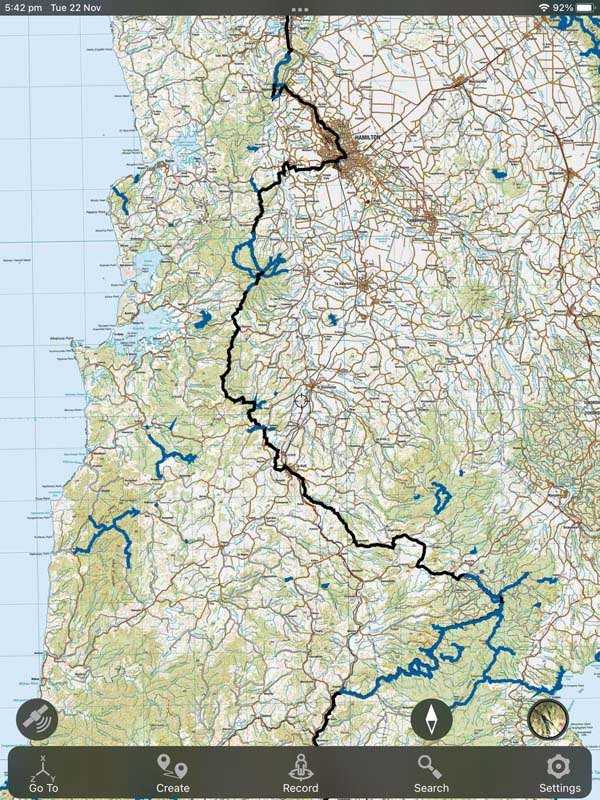

I am very well prepared for the Te Araroa with the relevant hard copy topo maps along with the trail notes telling me where to go and what to follow. I also have the topo50 app on my phone, all bases covered so how could I possibly get lost?

I am very well prepared for the Te Araroa with the relevant hard copy topo maps along with the trail notes telling me where to go and what to follow. I also have the topo50 app on my phone, all bases covered so how could I possibly get lost?

I wave goodbye and head off down the road, over a stile, across some farmland and into the forest. The track has an occasional orange marker, and is not at all obvious; and there are no markers in most places, in particular no markers where there is a choice of trail or where there seems to be no trail at all. Shouldn’t be a problem because I have my app with GPS pinpointing my position. I know at all times precisely where I am. However I discover that the black line marking the Te Araroa track on the topo50 is very approximate, so this amazing feature is not all that useful. Good for when I’m way off, but hopeless for precise trailblazing.

Very frustrating, although I don’t allow myself to become despondent. The other thing I realise is that there is no collective brain on this trip. It’s just me. I’m now used to tramping with others, mostly my grandchildren, whose observant, lightening fast brains notice the hidden detail. I find my way through the bush by brutal determination and end up where I’m meant to be at the road end marked in my notes. I didn’t bring my power pack and the cell phone is already half dead.

I walk the gravel road for hours, just walking, hardly wondering how I feel about my situation. Better not to feel anything at all when you’re uncomfortable, particularly if there’s no way out, which there isn’t, because this is what I wanted to do. I’m not happy, angry, discouraged or romantic. I’m just doing what has to be done. I’m unfit, which is unpleasant, and the route is an obstacle course. My trail notes direct me to turn off near where the road intersects with Oronga road but I walk straight past because in fact it is an unmarked access way up an embankment to a single house. I miss the nearby sign because a new larger sign broadcasting the new Forestry block is straight above. I keep on walking down the road until I really know I have gone too far. After a long backtrack I turn off onto broken farmland adjoining the young forestry block. Labouring over crumbling stiles, climbing gates, leaping creeks, I do wonder if I’m on the right side of the fence because it is all so awkward. I can’t cross over to see because the fence is a six feet high deer guard.

The hardest part is balancing on the moving number eight wire of old fences, pack on, trying to lift a leg over without wobbling too much. I’m walking steadily up with no mental space beyond immediate attention to where I am, wondering if I’m lost, and negotiating the next obstacle. Up near a second airfield I have to climb a 10-foot electric fence onto a 10-foot gate with my clumsy (for climbing) pack with front pouches, hiking poles thrown over, because I’m definitely on the wrong side. The electric part is only to waist height fortunately. I can do it, I can do anything and kind of enjoy the challenge, but it’s taking a toll on me. I need it to be easier at some point. The next orange-markered fence according to my directions doesn’t materialise, so I keep checking one fence line and then another, through scrub, over swamp, stumbling over half-buried fence palings, searching for a clue and using up more of my cell phone battery to check on the map.

The hardest part is balancing on the moving number eight wire of old fences, pack on, trying to lift a leg over without wobbling too much. I’m walking steadily up with no mental space beyond immediate attention to where I am, wondering if I’m lost, and negotiating the next obstacle. Up near a second airfield I have to climb a 10-foot electric fence onto a 10-foot gate with my clumsy (for climbing) pack with front pouches, hiking poles thrown over, because I’m definitely on the wrong side. The electric part is only to waist height fortunately. I can do it, I can do anything and kind of enjoy the challenge, but it’s taking a toll on me. I need it to be easier at some point. The next orange-markered fence according to my directions doesn’t materialise, so I keep checking one fence line and then another, through scrub, over swamp, stumbling over half-buried fence palings, searching for a clue and using up more of my cell phone battery to check on the map.

I’m tired and aching all through now. My feet are sore. This is to be expected. But my pelvis aches as if the pubic symphysis is about to tear apart. This is a brand-new malfunction.

At home I’d been telling friends that this walk would be like a meditation retreat, giving me time to contemplate in the quiet spacious heart of nature. Is there something I’m not seeing? One of my favourite sayings is, ‘There is no path – you make the path by walking.’

I set off down an unmarked track as my best guess. The topo50 app has totally thrown me off a couple of times. Finally an orange marker appears and I relax. The track meanders through the bush, lovely bush – I make a mental note, I don’t really experience the loveliness – before it re- emerges at a new fenceline, with four-wheel drive tracks the other side. I stay this side of the fence for hours it seems.

I started walking from Honekiwi Rd at 10:30am and it’s now 5:30pm and I’m still not down at the river where I was planning to camp. Fortunately I started out with two litres of water so I do have enough water for the night should I decide to stop here.

I bought a new tent for this trip which hasn’t left its bag. I need plenty of time to work out how to put it up. It is very beautiful so high up in these emerald hills. The sun is slowly sinking through the low cloud, the bush is settling quietly behind me, and the freshening wind is telling me I don’t have much time. I won’t get anxious, there is no need I’m sure, but I do have this brand new tent I haven’t pitched before, and a cooker I haven’t cooked on before. Not a comforting situation. It could feel exciting, but right now I would like my old well-used gear around me.

My super-light tent which uses trekking poles to stay up pulls out of its bag like slippery silk. There is nothing to it. It flutters into the wind like a dissolving cloud. I work out what to do easily with the guy ropes thin as string, and pegs tiny as pretzels. I bought it because it was so, so light. That’s really good. My back and shoulders are the only part of my body not complaining. But will it keep me safe from the wind and rain?

Down below my strictly practical mind, I’m awash in all the best memories of being alone in a tent on the land – a kind of conglomerate of happiness, freedom and bosom of nature stuff. I’ve returned to this tramping gig a lot older. I’d been told that all my super-best expensive tramping equipment from the eighties is obsolete. Lightweight and tiny is the way to go, and essential for me if I’m to keep doing what I love, and I do love slogging it out in the bush. I bought an Aarn tramping pack with front pouches to balance the weight, hiking poles, new USB headlamp, this new tent, two new water bladders, a new lightweight sleeping bag and Thermarest, lightweight tiny cooker and pots, super light raincoat, and thin merino thermals. And now I feel like a stranger in my own home because it’s all so brand new. But the land is familiar, this being alone on the land again, and I will do almost anything to end up here. This time it’s been a real trial and that is part of it. The sacrifice that is made, the being challenged, purified and broken so I can hardly lie down, that’s all part of it all. It makes the softness I now feel extra-ordinary. It takes only a few seconds to heat a packet of pumpkin and bean soup on my space- age cooker. That’s impressive and so is the eating, so matter-a-fact and totally magical that I can eat such delicious food out here.

Down below my strictly practical mind, I’m awash in all the best memories of being alone in a tent on the land – a kind of conglomerate of happiness, freedom and bosom of nature stuff. I’ve returned to this tramping gig a lot older. I’d been told that all my super-best expensive tramping equipment from the eighties is obsolete. Lightweight and tiny is the way to go, and essential for me if I’m to keep doing what I love, and I do love slogging it out in the bush. I bought an Aarn tramping pack with front pouches to balance the weight, hiking poles, new USB headlamp, this new tent, two new water bladders, a new lightweight sleeping bag and Thermarest, lightweight tiny cooker and pots, super light raincoat, and thin merino thermals. And now I feel like a stranger in my own home because it’s all so brand new. But the land is familiar, this being alone on the land again, and I will do almost anything to end up here. This time it’s been a real trial and that is part of it. The sacrifice that is made, the being challenged, purified and broken so I can hardly lie down, that’s all part of it all. It makes the softness I now feel extra-ordinary. It takes only a few seconds to heat a packet of pumpkin and bean soup on my space- age cooker. That’s impressive and so is the eating, so matter-a-fact and totally magical that I can eat such delicious food out here.

I am back inside the land and the setting sun and the cold wind by simply doing the practical necessities, empty of ordinary feelings, just letting my aching body onto the ground, a soft lumpy grassy bed, until I’m surrounded by the gossamer tent inner which keeps slipping through my fingers when I try to roll and hook it back. Everything is so light inside my tent. The sleeping bag is ever so soft and fluffy. The tent blows about in the wind, billowing and filling for lift-off, but I’m snug in here and when I zipper up for the night the billowing quietens down. Inside is filtered moonlight, and there’s plenty of room for my pack and food and spreading out of things. I’m hoping my miraculous body will heal and strengthen by morning, like it used to do in the old days when I was younger and stronger and even more foolish.

Morning arrives after much dreaming, a rich smorgasbord of my past swirling inside me. The tent has held up and the morning is cold and drizzly but I can see patches of blue sky. Now is okay. I say this to myself often in the bush, because my mind will be outspoken in less helpful ways given half a chance. Around the edges of sanity is an existential threat. I stay methodical. I roll and stuff and poke everything back into its proper place, no room for error or sloppiness.

Am I worried about the next part of the walk? I probably am. This whole adventure has a ‘getting lost’ signature. I’m sick of it. Why does getting lost matter? When I know where I’m going I just get there more quickly, that’s all – but I never pause, I’m off on the next part of the journey straight away, anyway. Maybe getting lost makes life more interesting. It challenges me in new ways. It can be exhausting. Is this how I actually live? We all walk by falling over. The first step throws us off balance and the next step catches us momentarily before it throws us off balance again, over and over. This is how we go forwards. Maybe life is the same. Maybe this is why I like walking. The more unbalance I can tolerate the faster I can move. Perfect balance is not the goal because then there would be no movement at all. Children love the game of learning to walk. They laugh at the joke of it, because the other side of their fear is so much more freedom.

‘There is no path. You make the path by walking.’ Actually I’m not sure there is a path. There is only experience. We make the path concept up to suit ourselves.

I set out along the fence line again, which turns abruptly straight down, back into the forest, orange markers all the way. That’s a relief. The track turns into a steep, slippery clay descent that is endless, with no orange markers but strips of orange ribbon tied to scraggly bushes. I assume that’s fine. I run out of descent and emerge close to a stream with one large orange marker pointing up the track to my left, and another orange marker pointing across the stream. I check both tracks thoroughly for a second orange triangle. None to be found, anywhere. I can’t use my topo50 app except for an emergency because the cell phone battery is almost dead. Both tracks have recent boot marks. I choose to head across the stream and up the right-hand track, straight up, because the written directions talk about crossing a stream and heading up, but the instructions suggest the stream is much larger than this one. It’s a good clear track, but unmarked all the way. I exit the forest back onto farmland, maybe not so far from where I headed down a few hours earlier. This is not where I meant to be, I’m sure of that. Where on earth am I?

I set out along the fence line again, which turns abruptly straight down, back into the forest, orange markers all the way. That’s a relief. The track turns into a steep, slippery clay descent that is endless, with no orange markers but strips of orange ribbon tied to scraggly bushes. I assume that’s fine. I run out of descent and emerge close to a stream with one large orange marker pointing up the track to my left, and another orange marker pointing across the stream. I check both tracks thoroughly for a second orange triangle. None to be found, anywhere. I can’t use my topo50 app except for an emergency because the cell phone battery is almost dead. Both tracks have recent boot marks. I choose to head across the stream and up the right-hand track, straight up, because the written directions talk about crossing a stream and heading up, but the instructions suggest the stream is much larger than this one. It’s a good clear track, but unmarked all the way. I exit the forest back onto farmland, maybe not so far from where I headed down a few hours earlier. This is not where I meant to be, I’m sure of that. Where on earth am I?

I open the topo app briefly to confirm my assessment. Now I’m officially not where I meant to be. I should be way down in the forest still, but it would be suicide to plunge back down now. I’m alive and out where I can definitely make a plan. I can orientate by the sun.

When I point the twelve o’clock on my watch (which is also brand- new) towards the sun, north is halfway between the hour hand and twelve o’clock. I need to head east, in the direction of Waitomo. I didn’t bring my compass, because I thought I wouldn’t need it, because I had my phone. To my left is the dark forest, and to my right, mountainous sheep country. It’s 10:30am and I’ve been walking for two and a half hours. My water bladders are full. I probably don’t need to be lugging this much water. My assessment of my situation is good. I’ll skirt the edge of the forest and look for a road of sorts. It could seem daunting, the vastness of this hill country, but I’ve been here before, and it never takes quite as long to cross the ranges as you think. I have a brief moment of excitement when a river meandering along below masquerades as a road. I keep walking up and down and around the smaller hills that are part of bigger hills. The sun tracks slowly across the heavens. Part of me is happy to be up so high, knowing inside I’ll be okay.

This is an adventure now, I’m making my own way, and I love it where the wind is fresh, and the land is without shadow. I track lower to the rushing stream, which curls around to confront me several times. I follow sheep tracks where I can because the pasture is hard and lumpy. I scan the forest for a sign, and then I see it, a gate in the perimeter fence. This has to mean something. I clamber down. It opens onto a good vehicle track through the bush. This will have a good ending. I wander along for a while before coming across a couple of dogs and then a woman and young boy by a stream. She is not surprised to see me. It happens quite often, she says. Maybe she would like to be annoyed, but she can see how desperately relieved I am to have discovered her. It’s a long way back to the road. We travel together for a while, her grandson in a pushchair constructed with bicycle wheels. I would go slowly now, as my thighs are screaming, but her pace is fast. She’s used to herding sheep all over these steep hills on foot, she says. I leave her near her home and keep walking the miles back to the road.

Where is the power I used to feel in walking? Walking under a hot sun, snacking on a muesli bar, sipping tepid water from my bladder, sinking onto the cool grass, using my poles to save my legs, gazing over the gorgeously green farm. Where is the freedom in this? At the road junction I turn left towards Waitomo. I don’t need to walk anymore – I need a ride. A woman with two grandchildren in the back picks me up almost immediately. ‘I don’t usually stop for hitchhikers but you looked like you needed a lift.’

I have weariness and dejection written all over me.

She’s driving back from the Waitomo Caves to visit her mother, the children’s great-grandmother, in Te Kuiti. She is planning to take her grandchildren blackwater rafting next. She talks about pot- holing, dropping down into little-known caves on private land. More importantly, she’s heading to Te Kuiti, which is exactly where I want to go. I have definitely abandoned my plan to camp near Waitomo and walk the route through the bush.

Out of the wind, on a bench seat in town, I pull out my phone. I have just enough charge left to ring Brian. As it happens he’s just around the corner at the RSA. Wow! I didn’t expect that. It’s all okay.

I can hardly walk the distance, crippled feet, aching body, dampened spirit. I hobble past the pool tables, collapse into a soft chair and wait for a cold beer.

In the morning, after a gentle night in the campervan at a Kiwicamp, we drive to Pureora Forest Park. I give up my plan of walking along the Mangaokewa river. My legs and feet really hurt. I’m expecting them to recover as the day warms up. I change into barefoot walking shoes so my creaking feet can spread and find their own way. I won’t give up. And I know the timber trail, I walked part of it last summer with Laura and grandchildren Asher, Aria and Scarley. We came down here after the Pirongia expedition. Brian cooks sausages and eggs again while I make the coffee. The repetition is disconcerting and comforting both.

Once again it’s a gorgeous morning, although the wind is icy. I stride off into the majestic forest, full of thousand-year-old totara, and other gigantic podocarps. Screaming kaka and sunlight streaking the leaves down to the gravel where I’m traipsing thirty metres below, is humbling and potentially inspiring, however my effort is with the walking and the cold. The track is well formed with markers every kilometre. I couldn’t be more happy and confident minus the limitations of my body. I’m on my way to Bog Inn hut, which is 20 km away, a six-hour walk.

Once again it’s a gorgeous morning, although the wind is icy. I stride off into the majestic forest, full of thousand-year-old totara, and other gigantic podocarps. Screaming kaka and sunlight streaking the leaves down to the gravel where I’m traipsing thirty metres below, is humbling and potentially inspiring, however my effort is with the walking and the cold. The track is well formed with markers every kilometre. I couldn’t be more happy and confident minus the limitations of my body. I’m on my way to Bog Inn hut, which is 20 km away, a six-hour walk.

I’m talking with a couple of cyclists at a lunch table, by a toilet for a civilised pause when it happens – still in shorts when the snow comes, when the light rain freezes and thickens, floating to white all around, like a magic show. We are all entranced, even though the couple are from Europe by their accents, and probably know snow quite well. My fingers are too cold to hold the hiking poles now, so I rest the poles on the front balance pockets. Most of my body pain has gone but I’m still very weak and don’t know why. The poles have been essential.

The forest is festooned with hanging mosses, dark and wet, raw and delicate everywhere I look. The snow settles on the branches. Although much of the bush surrounding me is regenerating it seems ancient. It took one lifetime to recover.

The walking is straightforward and doesn’t need my attention, but my mind won’t take up with thinking. It stays with the silent, dark forest. It stays empty. I’m not mulling over my past, the meaning of life, or the reasons I go tramping. I’m in a watery realm. Tree roots probing deep subterranean passages, water dripping from hanging mosses, zooming up the xylem, evaporating from the leaves, trickling down and under the track through plastic pipes, channelled into the deep cuts alongside the track, turning into snow fairies all around me. Thinking has absolutely no relevance here. I stay in the mesmerising rhythm of walking, the circling hips carrying my legs forwards, rolling feet impressing the ground, every part making small circles when I look closely, creating the spirals that cross through my body to swing my arms for balance. Walking is what humans do.

I arrive at Bog Inn hut around 5:30pm and have barely taken off my pack when a sudden battering on the tin roof starts up. A sudden downpour of hail turns to a fresh dump of snow and all becomes white outside. I only just arrived in time. Inside is freezing and dark. The small windows are grimy but it’s too cold to clean them. This is a very basic hut, four bunks, a table, some wire hanging from rafters to keep food out of reach of the rats, a tap, sink and bench outside. The wood stove is under repair. When I came here last summer with Laura and family we took the mattresses outside and slept under the high tree canopy and stars.

Staying warm is my number one priority. I put on my two super-light merino tee shirts, two light, long-sleeve merinos, black pullover, red polar fleece, and two sets of leggings. That’s all I have. I’ll be okay tonight. I’m not sure about tomorrow when I’ll be tenting. Experience has taught me not to worry about tomorrow, I just have to worry about today if I can even be bothered with that. Jesus recommended the same approach. He said ‘Don’t be anxious about tomorrow, for tomorrow will be anxious for itself. Sufficient for the day is its own trouble.’ This takes a lot of stress out of living. Maybe it’s another way of saying, ‘Don’t let the ego take over.’

I curl up in my cosy sleeping bag early for a long night, because there’s nothing else to do in this dark cold hut. I feel like I’m in a fairy tale, the maiden who has embarked on a solitary journey into the wild. I encounter hardship and my messengers. I’m curious about the women I’ve been meeting – younger grandmothers than me, reminding me of my fifties, when I felt powerful and useful and life was still full of promise. I am reminded where I have come from, but I still don’t know where I am going. I like that. I can give up on that. There is no journey, no path, there is just experience. I’m not going anywhere now.

I wake up to a very cold morning in the dark wooden hut. I don’t want to get up, it’s way too cold, but I must. Spilt water on the table is solid ice. I can’t turn the outside tap on. When I force it open no water comes out. Then I realise – it’s frozen. Fortunately I still have a little water in my bladder. My body feels good, aches and weak legs gone, but I’m still not strong like I remember. After filling my water bladders from the finger- freezing stream, I set out into a clear, cold, blue sky. The icy wind will soon arrive.

I cross two spectacular swing bridges, the bush tumbling over itself and pouring down the valley far below. I can’t believe that such bridges should exist, just for our pleasure. The bush is uproariously alive. It’s too much to really appreciate. So much time and money was spent to give us this forest to enjoy, for free. It’s overwhelming. And then a shelter, with toilets and picnic table and lawn flat enough for camping. In my younger days I might have spurned this as too tame. Now I let it all nourish me. Kakas shriek overhead, a river chatters away inside the bush.

I cross two spectacular swing bridges, the bush tumbling over itself and pouring down the valley far below. I can’t believe that such bridges should exist, just for our pleasure. The bush is uproariously alive. It’s too much to really appreciate. So much time and money was spent to give us this forest to enjoy, for free. It’s overwhelming. And then a shelter, with toilets and picnic table and lawn flat enough for camping. In my younger days I might have spurned this as too tame. Now I let it all nourish me. Kakas shriek overhead, a river chatters away inside the bush.

A couple of retired codgers roll up on a quad bike, passing the time. ‘The cold front has gone through, with good weather now for a couple of days,’ they say. Had I seen any deer? Really? Maybe deer tracks, but my eyes aren’t keen enough to spot deer now.

I pass more quad-bikes, laden with men and dogs. I think they’re remembering the good old days more than anything else. Being retired is not so easy.

Lunchtime is pivotal. It separates the energy of morning from the tiredness of afternoon. I’m on a sliver of grass by the track, just finishing my hard-boiled egg, two pieces of lettuce and Ryvita, about to snack on chocolate, when out of nowhere, that’s how it seems, another quad- bike with two much older men and three roaming dogs pulls up. The afternoon swells extravagantly. A large soft white dog bounds straight over to check out my meal. How cuddly and gentle he is. ‘They all have to pass the great-grandchildren test,’ the man says. They only become dangerous when there’s a pig. The dogs’ collars have GPS trackers, so the hunters can find them and the pig. I love how easy this all is, now I have paused, how wondrously ordinary, how hot the sun, how unconcerned the day.

‘Would you like a ride down to Piropiro? It’s a long way.’ Ten kilometres to go I estimate. I’m really tired but still determined to walk. My left knee screams on the downhill incline. The poles steady me. Bush and sun and a dusty road, mile after mile. This is what I imagined, just walking, the whole day through. Snacking, drinking, resting, softening, allowing the land and bush and wind and birds to soak me through – hardly noticing, just allowing. I’m being renewed because my body belongs to nature and it needs this time to remember. It gets disorientated in my normal life. And when I rest I’m as quiet and happy as can be, despite how hard the walking is. I’m surprised that it is. I should be strong by now, but I’m not.

I arrive as I knew I must, at Piropiro campsite. A couple of utes are leaving with at least ten quad-bikes on trailers behind. This is quad-bike central. It’s like a squatters’ camp here with makeshift buildings, an old container, tents and marquees and caravans, and lots of families. But this is a DOC campsite! The information board says there is no charge to visitors because volunteers look after the site. A kid on a trail bike zooms back and forth, revving and sliding about. I wonder if there’s an issue over the land ownership. Loud music starts up nearby. I’ve been told to expect temperatures of -3 to -4°. I set up camp. A group is playing footy nearby. Then a hammering starts up, and when it gets dark, a generator. This really is different from other DOC campsites. The water supply is a makeshift affair of wobbly black overflowing plastic containers and tap, attached to a pipe leading to a pump somewhere else. But I feel perfectly at home and when I get up to look around all I see is the space and bush. When I lie on the ground after my long day, everything unpacked, meal cooked and eaten, dishes wiped, water collected, I am totally happy. The moon is almost full and the evening is not freezing. I feel lucky to have won this gentle campsite for the night.

The morning is frosty-white, the tent fly crisp and crunchy. I was warm all night though. The fly is frozen to the inner in many places, and a few drips of thawing water land on the floor, but mostly it’s dry inside. The early sun blasts the fly, but how long can I wait for it to dry? As long as I need to warm up so I’m comfortable walking. The hours before lunch are the best walking hours, so I don’t want to wait too long. Within minutes the fly collapses onto the inner gossamer lining and soaks it through to the floor. I shove the soaking mess back into its bag. I stuff rather than fold this tent, like a sleeping bag, which is a real bonus for me. Planning the folds and rolls is always a trial, because it’s easy to fold too large or too small, so it doesn’t fit, and I have to repeat over. I will dry this drowned mess en route because pitching a wet tent at the end of a long day is no fun at all.

Walking is a real effort now. It’s been an effort all the way if I’m honest. I can’t find the power in my body I usually depend on. I suddenly realise I had COVID barely two months ago. It must have weakened me and exposed old joint issues. I remember reading about how COVID does exactly this. The inflammation response can drag on for a long time in debilitating ways. My body feels old, and it didn’t last summer. I hadn’t even considered this possibility. I hope this is temporary.

Today is my longest day. I’m walking 25 km instead of my normal 20 km but more of it is downhill, which is not necessarily a good thing given my cranky knee. The bush is breathtakingly grand. A few tufty- headed giants keep watch over their adult children, who in turn shelter the youngsters, all leaves turned for the sun. It’s all about the sun, in a way I don’t really know. Some part of me is separate from the forest. The majestic trees are aloof, inhabiting a different time, maybe no time at all, with different values or priorities, maybe not completely reducible to our ‘survival of the fittest’ sledgehammer. When I imagine water streaming up the xylem and the roots connecting with other trees through mycorrhizal fungal webs, I get a bit closer. The detail makes our relationship more personal. But the plant and animal kingdoms followed different evolutionary pathways. We have no idea the non-neural mind they may have developed. I love that.

As a child, I felt comforted by large trees, they seemed to understand my loneliness. The bush was like my mother, my place of refuge, the place I felt cared for and safe. I bonded with the sea in a similar way. My guardian angels were in nature.

I have two good tent drying stops during the day and drag the slippery silken sodden mess of a tent out over the dry grass while I snack and rest. Fortunately the sun is hot and the gossamer lining and nylon fly is soon afloat on the breeze. After seven hours of walking and resting I arrive at my last campsite No. 11. There’s a shelter, a toilet and a small patch of flat ground big enough for one small tent after I remove the blackberry wands. I’m totally alone in the vast forest spreading out in all directions. My heart aches with pleasure. A creek close by provides water. A group of chaffinches chatter, more curious than scared of me. It doesn’t get any better. The walking has been really hard, my body is stiff and sore now, particularly my feet, but none of this matters at all. All that matters is that I have arrived here.

I pitch the tent well. I’m getting to know its angles and preferences. I flick and twist and construct the cooker for a cup of tea, rather bemused. All this high-tech gear is for a younger generation. The bold colours, polished finish, slick coatings and super light materials don’t really suit me. I’m clunky and slow and awkward right now. Doesn’t matter. I’m grateful. The weight of my pack hasn’t been an issue. Because of the beneficent god of ‘lightweight’, my shoulders don’t hurt at all. Back on the ground I’m smiling all through, delighted for my simple freedom. The night is strangely full of bird chatter as is the dawn. The morning is overcast and the tent fly is saturated. I wonder how waterproof it is? Could this be just condensation? I don’t pause to dry it, or think too much about it, because I’m walking out today. I just stuff the dripping mass, twice its normal weight, back in its bag and put it on the outside of the waterproof inner at the top of the pack.

My body feels strong this morning – I’m clear and light-hearted – looking forward to a good final day – that is until I start walking. Then everything falls apart. My right foot collapses in pain when I roll forward onto the toes. My heel screams as if a hot knife has been stuck into it. My left foot joins it, yelling its discontent. My knee is yelling as well. I’m crippled. I don’t have any painkillers, I don’t even have a sticking plaster. I have plasters for the grandchildren in Lalita. I have my walking poles. I have to make this work. There is no way my feet will walk on their own. I start using my poles as legs, my arms doing all the work, forcing my feet to shuffle forwards like boards, locked at the ankles. I create a steady rhythm with the poles, so my feet are clear about what is expected of them. As soon as I slow down or break the rhythm, they freeze, incapable of moving forward on their own. This is a strenuous effort, a lumbering, forceful, disconnected gait, but I can do it. I can do it for the hours it will take. This is so humbling because I pride myself on using my body well. I do exercises to make sure the different parts of my body swing together and apart in an easy, integrated way. There are a lot of cyclists on the track. I pause before they see me.

There’s nothing I’d rather be doing than walking through this landscape, sending my gaze over the forest, smelling the damp of the deep cuttings, peering through the dark tunnel, following the cascading rivers, the rolling farmland, but not like this. It seems unfair, but it’s not of course. I’m grateful I can at least stumble the 15 km back to civilisation. The hours pass, I’m always amazed that they do. Time passes and if I keep walking I always get to where I’m heading, I just have to keep walking, falling over and catching myself, over and over, that’s the game. I can see the road end, a container for mountain bikes, a shelter and then … Lalita, the camper van. Brian is waiting for me with the chairs out on the gravel. He fills a glass with wine as I hobble into camp.

He wants to go straight home tonight though. He’s very uncomfortable sleeping in the van. I want to stay here longer, but it never seems to work that way. As we turn out of Otorohonga towards Pirongia, he tells me we have another student for my new printmaking class, so it will go ahead. Lalita carries us home as gently as she brought us here, so we could experience exactly what we set out to experience. My feet may be crippled but I’m ready to move forward again.

– Dyana Wells, Raglan Whaingaroa, New Zealand Aotearoa